17 May How Black History is Being Preserved in Williamsburg

As a family historian and founder of History Before Us, a project centered on capturing, preserving and advocating influential history, gathering oral history and conducting tireless research has been a staple of my innate being for the past 20 years. I’ve always been inquisitive about my family genealogy and how we settled in various southern states as part of the transatlantic and domestic slave trade.

Like many others, my family left the South during one of the many northern migrations for Blacks trying to escape Jim Crow, sharecropping, less-than-favorable wages, and inadequate educational opportunities. So how does this bring me to Williamsburg, you ask?

Years of sleuthing at county archives and visiting local libraries have helped me curate the origins of our family genealogy. I discovered that my great great grandfather, Wilson Pettus, was born in Virginia, and an exploration of Pettus matches on services like Ancestry.com and 23andMe provided additional confirmation that pointed me towards Williamsburg.

On the History Before Us blog, I dive even deeper into the specifics of my family genealogy research in Williamsburg (you can read it here). But for people who are interested in visiting Williamsburg to trace their own family roots–or simply learn more about how Black history is being preserved in the area–I wanted to highlight some impactful stops that I experienced during my recent visit to Williamsburg, Yorktown, and Jamestown.

Walking the “Great Valley” with a Yorktown historian

If you’re interested in exploring Historic Yorktown alongside a local historian, I’d recommend taking part in a Walking Tour of Yorktown, which picks up at Mobjack Bay Coffee Roasters. As part of my guided tour, I was able to walk the “Great Valley” footpath, which was rooted in debt to the enslaved who walked the same path after arriving in this foreign land via the transatlantic slave trade. The intrinsic feelings I experienced on this footpath were similar to when I first stepped foot on the former plantation where my ancestors were enslaved in Warren County, North Carolina. It elicited many thought-provoking moments and emotions: sadness, assumptions, inquisitiveness, anger, pride, motivation, and more. I’m forever appreciative to the souls who previously walked the “Great Valley.”

In addition to walking along the Great Valley footpath, I toured a site called Slabtown–also known as “Uniontown”–in honor of the Union Army. Beginning in 1863 and ending in 1976, Slabtown was a community that provided shelter, education, and guidance to African American citizens. As part of the Slabtown Walking Tour, visitors can take a step back in time by exploring streets and empty lots that once served as a close-knit community for those of African descent.

During the tour, I learned about residents like Dr. Daniel Norton, who were influential in cultivating a rich sense of pride, self-sustainability, and historical remembrance in this community. Dr. Norton, who escaped the institution of slavery in Williamsburg, became politically active and purchased large amounts of land in “Slabtown,” including 14 lots in Yorktown. His legacy is forever laminated in the community and the memory of those who adopt inspiration from existential examples of greatness.

Visiting the Historic First Baptist Church excavation site & the Sankofa Heritage Garden at Colonial Williamsburg

At Colonial Williamsburg, you will have the opportunity to see archaeologists exploring the site of the Historic First Baptist Church. The First Baptist Church of Williamsburg, one of the first African American congregations in the U.S., was founded by free and enslaved Black worshippers. As the excavation continues, the researchers are discovering more about how African Americans lived during Colonial times. During the first phase of its excavation, the foundation of the church (which was built in 1856) was unearthed, and phase two is currently underway to find other nearby structures and burials.

Standing on the grounds of the Historic First Baptist Church, I felt a sense of pride knowing that a group of enslaved and free Blacks at the start of the American Revolutionary War understood the importance of fostering community, no matter their legal status. This church provided refuge from the consistent threat of one’s holistic well-being during a time in which the majority had no legal rights or ways to advocate for themselves.

In recent years, there have been multiple instances in which discoveries of former sites related to Black history have come to light via tireless advocacy, research, and in some cases, happenstance. The Historic First Baptist Church is, fortunately, part of this collective currently being excavated. The excavation team is committed to amplifying the importance of this discovery, while members of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation and the Historic First Baptist Church continue to be the voice of parishioners, past and present. Williamsburg is lucky to have a community dedicated to a project that will influence the exploration and restoration of other Black religious establishments across the country.

Nearby is the Sankofa Heritage Garden, a replica of what garden plots of enslaved people would have looked like during that era. While exploring Colonial Williamsburg, visitors have the opportunity to tour the garden and learn about how innovative and non-wasteful the enslaved were, in addition to the types of gardening tools they used, what crops they harvested, and more. They used every square inch of the plots to create sustenance and autonomy, often at night, due to working for their enslavers during the day. The plots contained okra, basil, peanuts, peppers, and more. During a time in which cultural traditions were stripped, gardens such as the Sankofa Garden provided permanency for those who longed for the traditional resemblance of their homeland. My 86-year-old grandmother still gardens today and would be pleased to visit the site.

Visiting these historic sites invoked a sense of safety and belonging. The Black church obviously played a vital role in Black survival and existence, but in many ways, so did the act of gardening.

A glimpse of freedom at Freedom Park

Visiting Freedom Park was a stark reminder of what Black people longed for upon forced arrival in this country. The site was one of the country’s earliest Free Black Settlements, dating from roughly 1803 to 1860. Some of the families documented at the site were the Jacksons, Browns, and Lightfoots. These families were allowed to live on the land rent-free for 10 years, per the will of William Ludwell Lee, owner of the Green Spring Plantation. In 2002, the park opened to visitors, giving people a glimpse into the life of what some in the South may have thought to be unimaginable pre-Civil War. The site houses recreated cabins, furnishings, and farm equipment from that time period.

When I tour historic sites, I always inquire about descendants’ involvement. While there, I was pleased to learn that a local historian and descendant of those that lived on the Free Black Settlement, Col. Lafayette Jones Jr., wrote a book titled “My Great, Great, Grandfather’s Journey to an Island of Freedom.” The book details information on Jones’ ancestor and what life was like at the site. Freedom Park not only boasts rich Black history but also hiking and biking trails that create a true exploratory experience for families.

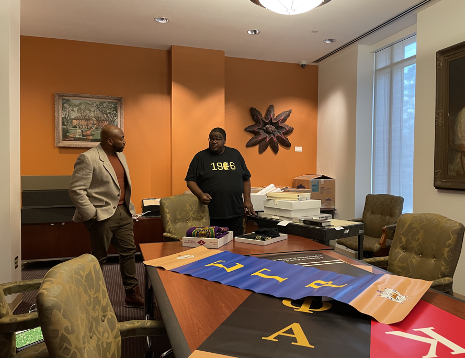

A chat with oral historian Andre Taylor at William & Mary

While in Williamsburg, I connected with Andre Taylor, an oral historian at William & Mary, to discuss his exhibit, “Strollin’: A History of Black Greek Letter Organizations at William & Mary,” which visitors can see at the Marshall Gallery of the Earl Gregg Swem Library until August 31.I previously visited William & Mary in 2019 as a presenter at an event organized by The Lemon Project, which is a program that was created to encourage scholarship on the university’s long history with slavery.

Andre is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, Incorporated, an African American Greek fraternity founded in 1906. I did not pledge a fraternity, but as a graduate of two Historically Black Colleges and Universities, I am well-versed in the importance and contributions of African American Greek letter organizations. Historically, many prominent African Americans have been members of the “Divine Nine” (the collective of Black Greek organizations), including Carter G. Woodson, Martin Luther King Jr., and Maya Angelou.

As a member of the “Divine Nine,” Andre developed the concept of an exhibit that focuses on the history and presence of Black Greek letter organizations at William & Mary. During our time together, I learned how the collection of oral histories was gathered from area fraternity members, viewed some of the special collections of historical items, and learned about the impact he hopes the exhibit will have.

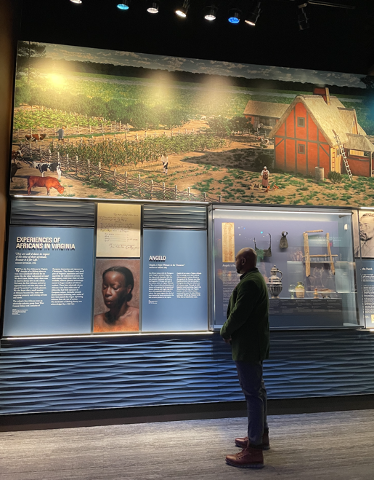

Discovering 17th-century history and culture at Jamestown Settlement

At Jamestown Settlement, I explored exhibits pertaining to those of African descent who were brought to the area by way of slavery or indentured servitude. As a board member of the Slave Dwelling Project, I’ve made it common practice to explore displays that highlight marginalized individuals who were part of the cultivation of wealth, sustainability, creativity, and innovation in this country. The museum boasts a variety of exhibits and artifacts that will enlighten those not well-versed on the likes of John Punch, an enslaved man who tried to escape colonial Virginia; Angelo, the first African American woman mentioned by name in the historical record at Jamestown; Phyliss Wheatly, the first African American–and American slave–to have their poetry published; Bacon’s Rebellion, and more.

From West Africa to the American Revolutionary War, the emphasis of African existence at the museum will surely help you develop a more comprehensive understanding of this rich history, not only in the region but across the globe.

Talking arts and culture with Steve Prince at the Muscarelle Museum of Art

It’s not often you meet someone with the artistic prowess of Steve Prince. He serves as the director of engagement and distinguished artist in residence at William & Mary’s Muscarelle Museum of Art, which is a laboratory for learning with over 5,000 artworks ranging from pre-Columbian to post-modern.

In 2017, Prince collaborated with his students to create a beautiful piece entitled “Lemonade: A Picture of America,” which pays homage to the first Black students in residence (1971). The piece commemorates the 50th anniversary of Lynn Briley, Janet Brown, and Karen Ely’s history-making moment. The exhibit is on permanent display in the Earl Gregg Swem Library as part of the President’s Collection of Art, which is open for viewing seven days a week.

He is also the maestro behind a sculpture called “Sankofa Seed.” The sculpture features a Sankofa bird, which represents the idea of looking at the past in order to move forward. The base of the sculpture comprises the names of William & Mary students who have made history at the college. You can find the sculpture located in the Legacy Tribute Garden outside of Jefferson Hall.

Exploring a replica slave dwelling at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown

The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown highlights the various roles that people of African descent played during the American Revolutionary War. Whether it was craftsmanship in iron-making or the cultivation of products such as sugar, tobacco, and other crops, these people helped fortify sustainability in colonial America and Britain. I feel like this is an area of history that is scarcely discussed, along with other factual historical events that leaned heavily on the existence and fortitude of people from the African Diaspora. In addition to exploring their presence in the war, you can also explore a replica slave dwelling featured at the outside exhibit. The dwelling and space depict the living quarters of the enslaved, which includes small garden plots used to grow vegetables native to their homeland. The museum is eclectic, providing interactive and traditional experiences.

The revival of Jolly’s Mill Pond with Angi Kane

My last stop in Williamsburg was Jolly’s Mill Pond. Angi Kane and her husband, Bill, are owners of the beautiful historic property, which in my opinion, is a national treasure. The sprawling site features a 50-acre pond and a 1/8-mile-long dam built over 200 years ago by the hands of enslaved labor. Interestingly enough, the site is just a short distance from the previously mentioned Freedom Park. Angi informed me of how her family gained ownership of the property and the importance of making it available for an immersive visitor experience. As guests explore the pond, they’ll find themselves captivated by nature and taken back to a time when the pond powered a gristmill and an industrial mill. It’s home to over a mile of trails, where guests can enjoy scenic views, birdwatching, and more. It’s also the perfect setting for hosting events (such as family reunions).

According to the Kanes’ research, a man named Jeremiah Wallace was the first owner of African descent. Land ownership after the Civil War was vital for African Americans. Despite the many obstructions and challenges faced by those who sought to own land, African Americans viewed land ownership as a route to true independence, and a confirmation of their freedom. This freedom and creative use of the land has carried through to the 21st century with Angi Kane becoming the second owner of African descent. As a couple, Angi and Bill are focusing on the site’s conservation, historical interpretation, community building, and environmental wellness. Angi, an Emmy award-winning filmmaker, is currently filming a docuseries highlighting the journey.

All good things must come to an end…for now.

The fact is, the soil and waterways in Williamsburg are filled with Black experiences that are steeped in pain, resilience, innovation, pride, and survival. The destination’s intentional efforts to bring its past to life through work with grassroots organizations reassures long-standing partnerships, education, marketing, and preservation. These essential actions will help increase visibility, making a more inclusive experience for visitors seeking Black history in the area. I’m honored to have met with so many people who are dedicated to assuring that these narratives are accessible to the masses and treated with great esteem. It was a breath of fresh air – so much so that I am already planning a return trip with my family this summer.

XXX

About Frederick:

Based in Charlotte, North Carolina, Frederick Murphy is the founder of History Before Us, a project centered on capturing, preserving, and advocating influential history, particularly African-American/American history. He searches for untold stories and enjoys research around genealogy. These untold stories prompted him to complete the award-winning documentary The American South as We Know It. He’s also a licensed professional counselor by trade, has a master’s degree in transformative leadership, and serves on the board of the Slave Dwelling Project, James K. Polk State Historic Site, and the Tennessee African American History Research Group.

No Comments